22 March 2021

Zartman's 'ripeness theory' provides a valuabe angle from which to assess case studies like the Bangsamoro Comprehensive Agreement and the necessary conditions for establishing successful negotiations in general. This could be useful for the new administration in Washington.

Full paper available as a PDF:

Abstract

The Biden administration is attempting to reshape American foreign policy in the Middle East, putting an end to costly interventions in both Yemen and Afghanistan by bringing the warring parties to the bargaining table. Such negotiations are never easy, yet there remains some successful case studies of national governments and Islamic terrorist organisations managing to negotiate peaceful outcomes, one of them being the Bangsamoro Comprehensive Agreement.

“If the enemy inclines towards peace, thou also incline towards peace and trust in God”

(Holy Qur’an VIII:61)

Introduction

A shift from violent action to peaceful means is neither an easy nor a clear-cut process since the use of violence demonstrates an underlining difficulty to peacefully achieve one’s political goals within the political system. Nevertheless, when two warring parties realise that weapons cannot bring about their desired outcomes, they engage in the process of negotiation. Negotiation theory has outlined how a “Mutually Hurting Stalemate” (MHS) and the presence of a “Way Out” produce the “push and pull” mechanisms needed for both conflict management and “ripeness” (Zartman 2008, p.232). Yet, negotiation theory often neglects to dig into those cases in which a perfectly ripe moment and a “ready-to-be-signed” deal get completely ruined by spoilers. Most specifically, it fails to provide a framework that presents the steps that negotiating parties must take to “re-ripen” a conflict and strike a deal, once the first window of opportunity is gone.

This essay will use the Mindanao case-study to explore how the Government of the Philippines (GPH) and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) managed to re-establish a fruitful negotiation process after their agreed-upon deal was declared unconstitutional by the Philippines Supreme Court. The essay’s framework will use Zartman’s (1989) “ripeness theory” as its starting point, and it will investigate the stages which allowed the transition from an MHS to Mutually Enticing Opportunity (MEO). This process is marked by the passage from “arms struggle” to “bargaining between two asymmetric powers” (Hopmann 1995; Zartman 2008; Albin 2012), characterised by specific strategic choices (Pruitt 1983), which should aim to reach the “problem-solving stage” while keeping spoilers under control. The MOA-AD’s failure in 2008 represented a low point in the GPH-MILF relationship, but the actors managed to re-establish trust, overcome past inadequacies and sign the Comprehensive Agreement on the Bangsamoro in 2014.

I. Conceptual Framework: Ripeness Theory

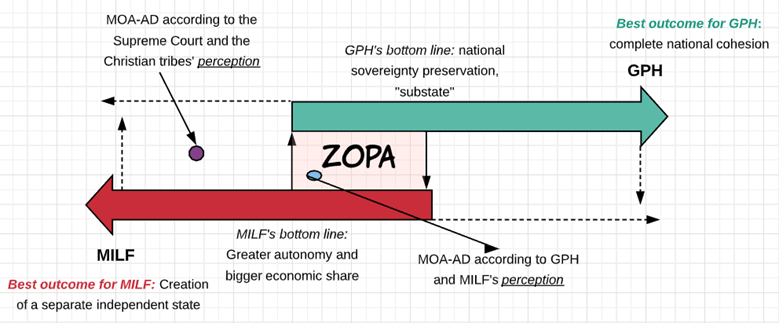

As explained by Zartman and de Soto (2010), mediation cannot be carried out at any random time: a conflict must be ripe for negotiation. Parties must find themselves in an uncomfortable and costly path, where the deadlock is felt as mutually painful because no one can escalate to victory (Zartman, de Soto 2019, p.5). The theory of “ripeness” focuses on the parties’ perception of a “Mutually Hurting Stalemate” (MHS), which leads them to seek an alternative solution, “a Way Out”. For ripeness to occur, both parties must perceive the situation of impasse as well as the common willingness to achieve a negotiated solution (Zartman and de Soto 2010, p.6). When going to the negotiating table, actors are aware of both their maximum expected outcome and their bottom line (Soo Kook 2011, p.186). The differences between their lows and highs consist in the “range of expectation”, and the overlap between the two ranges creates the so-called “Zone of Possible Agreement”, ZOPA (Soo Kook 2011, p.186), within which a deal can be struck.

As explained by Zartman and de Soto (2010), mediation cannot be carried out at any random time: a conflict must be ripe for negotiation. Parties must find themselves in an uncomfortable and costly path, where the deadlock is felt as mutually painful because no one can escalate to victory (Zartman, de Soto 2019, p.5). The theory of “ripeness” focuses on the parties’ perception of a “Mutually Hurting Stalemate” (MHS), which leads them to seek an alternative solution, “a Way Out”. For ripeness to occur, both parties must perceive the situation of impasse as well as the common willingness to achieve a negotiated solution (Zartman and de Soto 2010, p.6). When going to the negotiating table, actors are aware of both their maximum expected outcome and their bottom line (Soo Kook 2011, p.186). The differences between their lows and highs consist in the “range of expectation”, and the overlap between the two ranges creates the so-called “Zone of Possible Agreement”, ZOPA (Soo Kook 2011, p.186), within which a deal can be struck.

i. Bargaining between asymmetric powers

Negotiators of intra-state conflicts will often find themselves working within an asymmetrical environment. Interestingly, an asymmetry between parties can produce faster and better agreements which surprisingly tend to favour the weaker party (Zartman 2008, p.100). As a fact, powerful actors attempt to control their least powerful counterparts, using techniques like “take-it-or-suffer” that aim to worsen the weaker party’s security points (Zartman 2008, p.110-111). However, weaker parties often refuse their submissive role: they study the stronger party’s action and develop countermoves that aim to shake the strong party (Zartman 2008, p. 112). Negotiators of weaker parties can: borrow power from the stronger party by emphasising common interests/positions; borrow power from various third parties - adding value to their own position; and borrow power from the context, which gives the appearance of “levelness” and equal access to proceedings (Zartman 2008, p.113-114). Nevertheless, both parties have an ample range of strategic approaches to draw upon.

ii. Strategic choices in negotiation

Specific strategies impact the negotiation process in a different way. By assuming a distributive approach, parties will seek to reach an agreement through an exchange on concessions based on fixed positions (Albin 2012, p.271). Those negotiators use value-claiming strategies, based on a win-lose orientation, which aims to maximise their own gains at the expenses of the other’s (Albin 2012, p. 272). Alternatively, a negotiating party can assume an integrative approach, by seeing negotiations as an opportunity to solve a shared problem and applying value-creating strategies resulting from a win-win orientation (Albin 2012, p.271). As a fact, each negotiation presents mixed motives and the dilemma of the negotiator is to find the correct balance between the necessary flexibility to reach an agreement and the degree of firmness necessary not to be exploited (Hopmann 1995, p.39).

To such strategies, Pruitt (1983, p. 167) adds yielding, which entails a reduction of one’s basic aspirations, and inaction. Remarkably, problem-solving can be greatly beneficial when there is “momentum”, the presence of a mediator, trust – which can be developed - and when both parties maintain moderately high aspirations (Pruitt 1983, p.181). Yielding, on the other side, can be beneficial within a time-pressure environment, but if unbalanced, it can lead one party to win the lion’s share of the outcome (Pruitt 1983, p. 172). Yet, strategic tactics are not the only tools exploited to gain bargaining leverage.

iii. Ceasefires

To such strategies, Pruitt (1983, p. 167) adds yielding, which entails a reduction of one’s basic aspirations, and inaction. Remarkably, problem-solving can be greatly beneficial when there is “momentum”, the presence of a mediator, trust – which can be developed - and when both parties maintain moderately high aspirations (Pruitt 1983, p.181). Yielding, on the other side, can be beneficial within a time-pressure environment, but if unbalanced, it can lead one party to win the lion’s share of the outcome (Pruitt 1983, p. 172). Yet, strategic tactics are not the only tools exploited to gain bargaining leverage.

iv. Spoilers management

Bargaining between asymmetric powers and the choice of correct strategic behaviours are big challenges for negotiators. Still, all their efforts can be ruined due to a spoilers mismanagement. Indeed, negotiations can be damaged by total spoilers, who radically oppose any settlement of the conflict; greedy spoilers, who aim to prolong the conflict to gain material advantage from the current environment; limited spoilers, who impede the peace process to improve their relative position in the deal (Stedman 1997, p.15). The presence spoilers can lead to a deal’s failure, as occurred with the MOA-AD in 2008. Thus, a correct analysis of spoilers is fundamental for appropriate management: total spoilers must be defeated or marginalised through a “departing train strategy”, which entails a delegitimisation of spoilers and a deprivation of the sources they use to ruin peace (Stedman 1997; p.14). Greedy spoilers can be included in the deal if the costs of war are elevated. Their management requires a long-term strategy of socialisation, in which negotiating parties must distinguish between legitimate and illegitimate demands, and “coerce” spoilers to limit their requests (Stedman 1997; p.15). Finally, limited spoilers can be dealt with, by meeting their non-negotiable demands through inducement (Stedman 1997; p.14).

This framework will guide our understanding of the Bangsamoro peace negotiation.

II. MOA-AD and the Bangsamoro Comprehensive Agreement in the Philippines

The struggle of the Moros finds its roots in the Treaty of Paris of 1898, when Spain ceded the Philippine archipelago to the United States, despite the fact it had never exercised full sovereignty in the areas of Mindanao and Sulu, two sultanate-based islands (Bayot 2018, p.5). The forced annexation to the “Philippine state” resulted in the marginalisation of the Moros and other Non-Christian tribes, further exacerbated by decades of government neglect, the exploitation of natural resources and the dispossession of Moros’ native lands through Christian resettlement programs (Bayot 2018, p.6). The Bangsamoro rebellion has at its essence the issue of autonomy: a battle between the Philippine government pushing for more national unity and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front pushing for greater independence (Bayot 2018, p.6).

The MOA-AD, the Memorandum of Agreement of Ancestral Domain, was meant to represent the culmination of eleven years of peace negotiations between GPH and MILF, solving the core issues of governance, resources and territory (Soo Kook 2014, p.165). Nevertheless, due to the high expectations from their opponents, the two negotiating parties agreed on terms that exceeded what politicians and the public were ready to give up (Soo Kook 2014, p.166). Consequently, the Philippines Supreme Court defined the deal “unconstitutional”, claiming that the “associative relations between the government and the Bangsamoro Judicial Entity (BJE)” and the concept of “substate” constituted a threat to the Philippine sovereignty (Soo Kook 2014, p.172). Thus, MOA-AD surpassed the bottom line, attracting “neglected” spoilers – unamused by changes that the deal would have brought in the power structures of Mindanao.

^ Figure 1 ZOPA between MILF and GPH

Thus, MOA-AD failed to be signed, bringing a ripe conflict back to phase 1: military struggle. Violence was renewed in Central Mindanao, primarily carried out by the battalions of Commander Bravo, Pangalian and Kato, command-leaders of the Bangsamoro Islamic Armed Forces of MILF (Pobre and Quilop 2008, p.119). This rogue violence triggered the Armed Forces of Philippines (AFP) to counter-act through the operation “Lightning Sword”, a punitive campaign meant to defeat the MILF through two Unified Commands in Mindanao (Pobre and Quilop 2008, p.128). Such campaign, however, did not lead to the hoped results: AFP was using semi-conventional tools such as standard-planning, troop disposition and deployment, but insurgents fought following guerrilla warfare, aiming not to kill the opponent in one stroke but “to bleed him and feed on him” (Pobre and Quilop 2008, p.128). The military troops understood that the unorthodox attempt to “exterminate” MILF could not deliver the expected outcomes; similarly, due to the asymmetrical power between the parties, MILF recognised that “making the dog bleed” could never convert into “arm victory” (Pobre and Quilop 2008, p.161). Thus, a new mutually hurting stalemate had been created.

In 2009, MILF surprisingly proclaimed a unilateral ceasefire. This ceasefire was used as a tool to regain bargaining power (Stichter & Vukovic 2019, p.10). Indeed, MILF was interested in gaining international legitimacy and by putting the GPH in the spotlight, it would have ensured that any “future missed deal” would have been severely judged by the international community Pobre and Quilop 2008, p.172). The proclamation of the ceasefire was also accompanied by some requests: the complete end of military attacks against MILF; the presence of the International Monitoring Team for ceasefire supervision; the use of the Malaysian negotiators as third party facilitators (Pobre and Quilop 2008, p.170).

The bargaining between MILF and GPH, ready to be re-started, was demarcated by a clear asymmetry of powers. GPH was stronger in terms of geographical size, GDP and military personnel – but MILF managed to move it towards its desired direction, by improving its relative power (Zartman 2008, p.112). Indeed, the use of Malaysia as intermediary served to borrow power from the context: Malaysia had a special interest towards the Moro cause due to a land dispute over the Malaysian area of “Sabah”, which was once Philippine (Park 2014, p.56). MILF exploited the Malaysian bias to increase their power while serving the Malaysian national interest by lifting its reputation within ASEAN and by developing a convenient good relationship with his neighbour-ally.

The bargaining stage was also shaped by a change of leadership. At the government, Gloria Arroyo was replaced by “the Teflon President” Benigno Aquino III, who had decided to approach peace in a more malleable way (Wilhelm 2014, p.28). Similarly, MILF learnt during the years of negotiation that “independence” was not achievable – and while MOA-AD had not succeeded, any autonomy greater than the one granted to the Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao (ARMM) was sufficient to motivate MILF towards negotiations (Park 2008, p.60). Consequently, the combination of the Malaysian mediation, a newly elaborated ceasefire and two “eager” leaderships, created the conditions which made the conflict ripe for both parties. Additionally, a MEO” of future benefits was also added when the EU donated 7 million euros to Mindanao as a way to repair the conflict’s damages and as an incentive for future benefits in times of peace (Pobre and Quilop 2008, p.194).

The strong desire to “win peace”, and the external mediation, induced the Aquino government to open the floor with an integrative approach, ditching value-claiming strategies aimed to maximise the government’s gains. Interestingly, the government’s initial counter-demand that the “MILF surrendered its rogue commanders after the 2008 attacks” was retrieved, presented as no longer a negotiation “precondition” (Pobre and Quilop 2008, p.170). This behaviour resembled Pruitt’s (1983, p. 167) yielding technique, i.e. a reduction of a party’s underlying goals as a strategy for problem-solving. Pruitt (1983, p. 167) explains that yielding is usually exploited during periods of “time pressure”, and the reasoning perfectly matches Aquino’s desire to strike a deal, and complete any transition process, before the end of its mandate in 2016 (Park 2008, p.60). Thus, the government appeared so fixated on having a new agreement that it did not care about its relative costs – except for the non-negotiable pre-condition “to keep one flag for one country” (Pobre and Quilop 2008, p.174).

The bargaining took the form of “principled negotiations”: both parties started with a joint diagnosis of the problem, followed by an effort to find a working formula which addressed their shared issue (Hopmann 1995, p.41). This process was also meant to address the problem of spoilers: MOA-AD failed because the whole Philippine population was not consulted. The negotiated peace had to result from a consensus of all the people living in the concerned areas, and all the citizens should have transparent access to the deal – rather than keeping it secret, as it was done for the MOA-AD (Williams 2010, p.135). Thus, the Malaysian mediation first tried to handle total spoilers, i.e. those utterly against any deal. It adopted a “departing train” strategy against the Abu Sayyaf Group and the Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Fighters, which consisted in the delegitimisation of the groups and in labelling them as terrorists (Park 2008, p.62-63). The negotiations also tried to tackle the MNLF: the group is a total spoiler within the peace deal, however, mediators have chosen a “facilitation approach” which aims towards a benign fusion of MNLF-MILF, since only their convergence will allow any deal to be sustained on the long-term (Fajans-Turner 2011, p.196).

The parties also realised the importance of handling the greedy spoilers, the “datus”, i.e. Moro clan leaders exploiting their resources to gain wealth from corrupted economic practices. These politicians had teamed up with the Christian communities in the North to stop MOA-AD in 2008, since its introduction would have taken their powers away (Olympiou 2014, p.139). Negotiators knew that peace needed support through various sectors of society, thus they devised a “socialisation” technique, including these greedy spoilers in the governance mechanisms of peacebuilding advocacy (Abubakar and Askandar 2019, p.169). Finally, for the deal to be effective, it had to consider the presence of limited spoilers: the Christian communities and the Indigenous People. While the MOA-AD meant to improve the situation of the Moros, “it does not consider the ancestral domain claim of the Tedurays, the Dulangan and Manobo – the other ethnic groups” (Rodil 2008, p.5). Thus, the negotiators, through the civil society setting, involved in dialogue Christians, Moros and ethnic groups to “negotiate and decide how best create an interdependent, not independent, resolution to the conflict” (Morgan 2004, p.9-10 in Pobre and Quilop 2008, p.211).

As a matter of fact, all these settings allowed GPH and MILF to finally agree and sign the Bangsamoro Comprehensive Agreement in 2014.

III. Conclusion

When a deal worth eleven years of negotiations fails to be signed, violence, confusion and loss of hope inevitably spread among the negotiating parties and the population. Is it possible to recreate the proper ripeness once the window of opportunity is gone? The Moros struggle and the long-lasting battle between GPH and MILF demonstrate that negotiations can be resumed, and a negotiated peace agreement can be attained. However, the conflict must first run its course, and both parties must first find themselves in an MHS. Once this position is reached, the key steps involve the use of those bargaining techniques and strategic tools which allow the negotiators to address the problems which caused the failure of the previous deal. Mindanao demonstrated the necessity to build trust, manage correctly every kind of spoiler and assume a transparent approach which accounts for the struggles of the whole Bangsamoro people – Moros, Indigenous and Christians. Only in this way, an interdependent and comprehensive resolution of the conflict was achieved.

Bibliography

Abubakar, A., Askandar, K. (2019), ”Chapter 9: Mindanao”. In Alpaslan Özerdem, Roger Mac Ginty (2019) “Comparing Peace Processes”. First edition, London Routledge.

Albin. C. (2012). “Explaining Failed Negotiation: Strategic Causes”, in Faure, G.O. (ed.) Unfinished Business: Why International Negotiations Fail. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, pp. 269-282.

Bayot, A. B. (2018), “Elite Bargains and Political Deals Project: Philippines Case Study”. Stabilisation Unit

Fajans-Turner, A. (2011), “Section 3, Part 14: Autonomy and the ARMM”. In Chavez et al (2011)

“Mindanao: Understanding Conflict 2011 Conflict Management Program Student Field Trip to Mindanao”. Edited by Dr. P. Terrence Hopmann and Dr. I. William Zartman

Hopmann, P.T. (1995). “Two Paradigms of Negotiation: Bargaining and Problem Solving”, The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political Science, Vol. 542: 24-47.

Olympiou, O (2014), “Section 3, Part 12: Potential Spoilers in Mindanao”. In Anis et al (2014), “Mindanao: Understanding Conflict 2014 Conflict Management Program Student Field Trip to Mindanao”. Edited by Dr. P. Terrence Hopmann and Dr. I. William Zartman

Park, M. (2014), “Section 2, Part 5: “Malaysian Mediation in the Framework Agreement on the Bangsamoro”. In Anis et al (2014), “Mindanao: Understanding Conflict 2014 Conflict Management Program Student Field Trip to Mindanao”. Edited by Dr. P. Terrence Hopmann and Dr. I. William Zartman.

Pobre, C. P. and Quilop, R.J.G. (2008), “In Assertion of Sovereignty: the Peace Process. Volume Two”. Office of Strategic and Special Studies Armed Forces of the Philippines

Pruitt, D. G. (1983). Strategic Choice in Negotiation. American Behavioral Scientist, 27(2), 167–194. https://doi.org/10.1177/000276483027002005

Rodi, R.R. (2008), “The Indigenous Peoples and National Security,” Lecture presented during the Roundtable Discussion on the Role of the Indigenous Peoples in National Security, National Defense College of the Philippines, Camp Aguinaldo, Quezon City,

Stedman, S. J. (1997). “Spoiler Problems in Peace Processes,” International Security, Vol. 22, No. 2, pp 5-53.

Soo Kook, K. (2011), “Section 3, part 13: Peace Talks in Mindanao: What do They Really Want?”. In Chavez et al (2011) “Mindanao: Understanding Conflict 2011 Conflict Management Program Student Field Trip to Mindanao”. Edited by Dr. P. Terrence Hopmann and Dr. I. William Zartman

Stichter, V. & Vukovic, S. (2019), “From War to Peace: The Subtle Role of Ceasefires”. working paper.

Zartman I.W. (2008), Negotiation and Conflict Management: Essays on Theory and Practice,

Zartman, I.W., de Soto (2010),” Timing mediation initiatives”. The Peacemaker’s Toolkit Series Editors: A. Heather Coyne and Nigel Quinney

Wilhelm, C (2014), “Section 1, Part 3: Identity Politics: The MNLF, the MILF, and What Their Differences Mean for the Transition. In Anis et al (2014), “Mindanao: Understanding Conflict 2014 Conflict Management Program Student Field Trip to Mindanao”. Edited by Dr. P. Terrence Hopmann and Dr. I. William Zartman.

Williams, T. (2010). The MoA-AD Debacle – An Analysis of Individuals’ Voices, Provincial Propaganda and National Disinterest. Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs, 29(1), 121–144. https://doi.org/10.1177/186810341002900106