28 September 2022

Social media has become a hotly contested space for information warfare. If state actors intend to seize the narrative, they must adopt appropriate strategies for countering misinformation.

We recommend reading this piece in its PDF format so that you have access to the footnotes

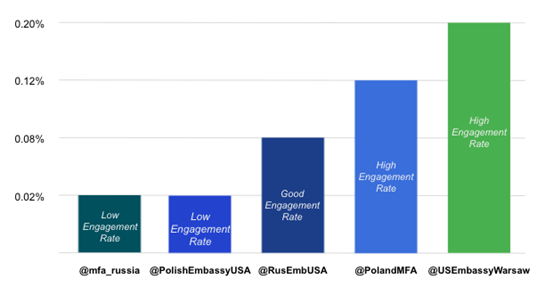

Bjola refers to this kind of CSD tactic as ‘ignoring.’ Diplomats ignore disinformation to prevent escalation (Bjola, 2019). While it is understandable for diplomats to ignore targeted disinformation, this tactic allows fallacious statements to go undisputed. Given that @USEmbassyWarsaw has a high engagement rate, it should be practicing digital diplomacy to disseminate positive western narratives to counter misleading ones.

Engagement Rate of Twitter Campaigns

This chart provides the average engagement rate of each hashtag campaign

^ Graph by author.

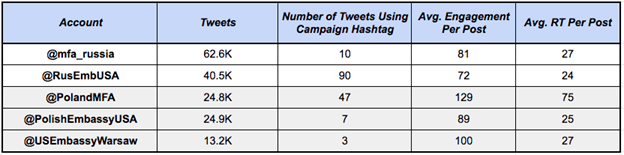

In contrast, @PolishEmbassyUS deployed the hashtag seven times and amassed a relatively low engagement rate compared to @USEmbassyWarsaw.

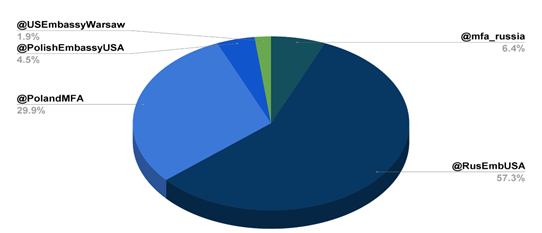

Percentage of Tweets Using Designated Campaign Hashtag

This chart shows the differences in tweet frequency by account between September 1, 2019, and March 31, 2020.

^ Chart by author

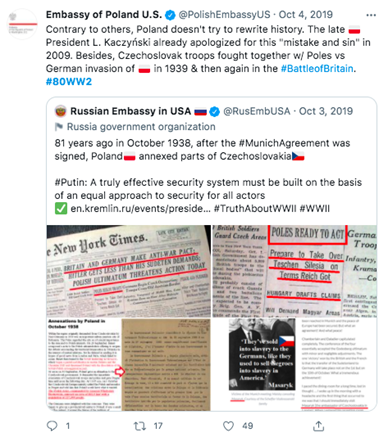

The Polish Embassy used the #80WW2 campaign to discredit Russian officials for attempting to rewrite WWII history. Bjola refers to this tactic as ‘discrediting,’ which seeks to undermine the messenger’s credibility (Bjola, 2019). However, given skepticism of Western propaganda in Russia and surrounding regions, such measures may motivate pro-Russia actors to adopt more aggressive disinformation strategies (Helmus et al., 2018: 71-73).

Polish Embassy in the US (2019) [Twitter]

@PolandMFA’s used the #80WW2 campaign to recount the history of Poland during WWII. Through 47 tweets over 18 days, @PolandMFA’s covered the near entirety of WWII from 13 major battles to individual stories of victims, paid homage to underground units, and resistance organizations, recognized the role of Polish radio stations during the conflict, and reviewed the post-war order. Unlike Russia’s disinformation campaign that criticized and accused Poland of falsehoods, the Polish campaign was objective and made sure to recognize the Soviet’s pivotal role in helping the Polish Army. Bjola claims that presenting facts accompanied by visuals to offer an alternative narrative rather than simply refuting misleading claims can help counter disinformation more effectively (Bjola, 2019).

Despite Poland’s effective counter-messaging strategy reviewed above, Bjola does not recognize @PolandMFA’s use of the campaign as one of the five CSD tactics. Perhaps @PolandMFA’s digital strategy could be referred to as ‘Neutralizing’ through the way it uses digital diplomacy to offset narratives designed to depict a manipulated view of reality. The way in which @PolandMFA used the campaign and Twitter as a storytelling medium to provide an alternative narrative to Russia’s account was well-received among its followers.

Twitter Campaign Engagement Metrics

This table demonstrates relevant metrics regarding each Twitter account’s hashtag campaigns.

^ Table by author.

Its campaign provided its followers with a focused narrative that shared facts via compelling visuals and recognized the value of Western allies. Additionally, the data reveals that @PolandMFA’s campaign generated an average of 57% more engagement per post than 14 @RusEmbUSA’s campaign. Retweets are telling of follower-receptivity and help amplify particular messages by transferring them to a different audience. In the future, embassies can use @PolandMFA’s counter-messaging campaign as a framework to neutralize the threat of disinformation.

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Poland (2019) [Twitter]

This case study is important because it illustrates how Putin’s stab at historical revisionism indicates his willingness to alter past narratives to shape future foreign policy (Bankauskaitė, 2020: 1). These disinformation campaigns target younger generations with little to no memory of WWII who are more vulnerable to manipulation. Lea Gabrielle, Special Envoy and Coordinator of the GEC, reiterated the international necessity to communicate truthful narratives about WWII, and counter Russia’s historical revisionism (US Department of State, Gabrielle Testimony 2020). With the ebbing of those who lived through WWII, the story runs the risk of not being remembered or told factually, which is why it is crucial to carry out counter-messaging campaigns like #80WW2. Doing so preserves an authentic and accurate recollection of history for those who may not be familiar with WWII or understand how it relates to the EU-US bilateral relationship today.

Discussion

This case study demonstrates that diplomatic institutions can implement more effective measures to counter pro-Kremlin disinformation on social media. The challenge of weaponizing information is that governments who fail to set the message straight in cyberspace risk allowing misleading narratives to go unchallenged and therefore leading to mass acceptance of a threatening alternative. Thus, the goal of digital diplomacy in CSD is to ensure the robustness of optionality in the digital public sphere (Powers & Kounalakis, 2017: 30). However, not every disinformation campaign requires a public diplomacy response. In some cases, countering disinformation can backfire and may amplify a disinformation campaign (Subcommittee Hearing, 2020: 44). Skeptics argue that there is a lack of evidence suggesting pro-Kremlin disinformation’s ability to sway public opinion (Nemr & Gangware, 2019: 18).

Disinformation is not solely a domestic threat; it is a global one that demands cooperation. To counter disinformation, states must collaborate with allies who have shared values and understandings of the threat (Jean-Baptiste, 2021: 9). On one hand, behavioral analysts argue that the best way to counter pro-Kremlin disinformation is by crafting clear, compelling, and consistent digital narratives that offer a Western perspective to tell the EU, US, and NATO message to a broader audience (Helmus et al., 2018: 88-90). On the other hand, policymakers deem proactive approaches to CSD, such as media literacy training and advocacy, more effective in cultivating long-term societal resistance to disinformation (Walker & Walsh, 2020: 6).

While there is no one-size-fits-all approach to CSD, it is widely recognized among experts and senior public diplomacy officials that in an increasingly digital world, person-to-person interactions, such as conferences and educational programs, are not enough to counter a threat that is digital in nature. Future diplomatic efforts should prioritize and incorporate digital proficiency (Walker & Walsh, 2020: 37). Although it appears as if one country’s information campaign is another country’s disinformation operation, it all boils down to intent. Digital tools present a dualuse provocation. As observed in the case study, digital diplomacy can be used to communicate truthful information via soft power approaches just as easily as it can be used to disseminate disinformation or misinformation through sharp power strategies.

Conclusion

While research into disinformation has received a great deal of attention, there is still much to learn in terms of crafting a sophisticated counter-strategy. This paper considers the role that US diplomatic institutions play to help combat pro-Kremlin disinformation on Twitter. It revealed how diplomatic institutions should master the art of digital diplomacy to offset and rectify disinformation in addition to traditional proactive measures. For other Western states facing similar threats to democracy, this analysis can serve as a model for how diplomatic institutions use counter-messaging campaigns on social media to promote and safeguard their image from targeted disinformation. In sum, ideological information wars cannot be won by sanctions or military deterrence alone. Effective solutions must involve investments in soft power strategies such as skillful public diplomacy and its digital counterpart. In the future, US diplomatic countermessaging efforts should coordinate with the intelligence community to ensure that political concerns are considered.

In a world where emerging world leaders are running for office and the dissemination of disinformation is rampant, the need for truthful information is as vital as food and water. The Kremlin has no intention of slowing down its disinformation campaigns. To address the looming threat of state-sponsored disinformation, it is imperative that MFAs and embassies maintain an active presence in the digital sphere so that, if necessary, they can adequately devise culturally relevant digital campaigns that work to neutralize disinformation by offering clear and truthful narratives about their country and its values. Just as the Cold War required diplomats to harness the power of public diplomacy to combat the spread of Soviet propaganda via radio, the post-truth era requires government officials to harness the power of social media to combat pro-Kremlin disinformation. Traditional means of communication are not enough to counter today’s information wars. In the new media age, 21st-century battles need to be fought and countered digitally on the very platforms in which they originate.

Bibliography

Adesina, O.S. (2017). Foreign policy in an era of digital diplomacy. Cogent Social Sciences, 3 (1)

Aiken, A. ed., (n.d.). RESIST Counter-disinformation toolkit. [online] Government Communication Service. Available at: https://gcs.civilservice.gov.uk/publications/resist-counter-disinformation-toolkit/.

Bankauskaite, D. (2020). Op-Ed: Disinformation about history leads to disinformation about the present. [online] Medium. Available at: https://medium.com/dfrlab/op-ed-disinformation-about-history-leads-to-disinformationabout-the-present-a6ddce4b618.

Bjola, C. and Pamment, J. (2016). Digital containment: Revisiting containment strategy in the digital age. Global Affairs, 2(2), pp.100–142.

Bjola, C. (2019). The “Dark Side” of Digital Diplomacy | USC Center on Public Diplomacy. [online] Available at: https://uscpublicdiplomacy.org/blog/dark-side-digital-diplomacy

Bjola, C. and Papadakis, K. (2020). Digital propaganda, counterpublics and the disruption of the public sphere: the Finnish approach to building digital resilience. Cambridge Review of International Affairs, pp.1–29.

Bodine-Baron, E., Helmus, T., Radin, A. and Treyger. (2018). Countering Russian Social Media Influence. RAND Corporation. [online] Available at: https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR2700/RR2740/RAND_ RR2740.pdf.

Bos, M. and Melissen, J. (2019). Rebel diplomacy and digital communication: public diplomacy in the Sahel. International Affairs, 95(6), pp.1331–1348.

Bradshaw, S. and Howard, P.N. (2019). The Global Disinformation Order 2019 Global Inventory of Organised Social Media Manipulation. [online] Available at:

https://demtech.oii.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/93/2019/09/CyberTroopReport19.pdf.

Bradshaw, S., Neudert, L.-M. and Howard, P.N. (2019). Government Responses to Malicious Use of Social Media. [online] Programme on Democracy & Technology. Available at: https://demtech.oii.ox.ac.uk/research/posts/government-responses-to-malicious-use-of-so cial-media/#continue.

Buziashvili, E. (2019). Russian diplomatic Twitter accounts rewrite history of World War II. [online] Medium. Available at: https://medium.com/dfrlab/russian-diplomatic-twitter-accounts-rewrite-history-of-worldwar-ii-3d86c441d10d#0cf0.

Cross, M.K.D. and La Porte, T. (2017). The European Union and Image Resilience during Times of Crisis: The Role of Public Diplomacy. The Hague Journal of Diplomacy, 12(4), pp.257–282

Elswah, M. and Howard, P.N. (2020). “Anything that Causes Chaos”: The Organizational Behavior of Russia Today (RT). Journal of Communication.

EUvsDisinfo. (2019). Breaking “News”: The Kremlin Discovered that Poland Started WWII and the Baltics Are Not Free. [online] Available at: https://euvsdisinfo.eu/breaking-news-the-kremlin-discovered-that-poland-started-wwiiand-the-baltics-are-not-free/

EUvsDisinfo. (2020). In the Shadow of Revised History. [online] Available at: https://euvsdisinfo.eu/in-the-shadow-of-revised-history/.

EUvsDisinfo. (2020). Kremlin Historians, Fighting the War on Remembrance. [online] Available at: https://euvsdisinfo.eu/kremlin-historians-fighting-the-war-on-remembrance/

Gaida, F., Efremenko, D., Lomanov, A., Miller, A., Teslya, A., Filippov, A. and Lukyanov, F. (2019). Historical Memory is Another Space Where Political Problems are Solved. [online] Russia in Global Affairs. Available at: https://globalaffairs.ru/articles/istoricheskaya-pamyat-eshhe-odno-prostranstvo-gde-resha yutsya-politicheskie-zadachi/.

Global Engagement Center, 2020. Pillars of Russia’s Disinformation and Propaganda Ecosystem. (2020). [online] Available at: https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Pillars-of-Russia%E2%80%99sDisinformation-and-Propaganda-Ecosystem_08-04-20.pdf.

Golovchenko, Y. (2020). Measuring the scope of pro-Kremlin disinformation on Twitter. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 7(1).

Halliday, J. (2014). BBC World Service fears losing information war as Russia Today ramps up pressure. [online] The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/media/2014/dec/21/bbc-world-service-information-war-rus sia-today.

Hanson, F. (2012) Baked in and wired: eDiplomacy@State. [online] Available at: https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/baked-in-hansonf-5.pdf.

Hedling, E. (2021). Transforming practices of diplomacy: the European External Action Service and digital disinformation. International Affairs.

Helmus, T., Bodine-Baron, E., Radin, A., Magnuson, M., Mendelsohn, J., Marcellino, W., Bega, A. and Winkelman. RAND Corporation. (2018). Russian Social Media Influence Understanding Russian Propaganda in Eastern Europe. [online] Available at: https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR2200/RR2237/RAND_ RR2237.pdf.

Kenney, C., Bergmann, M. and Lamond, J. (2019). Understanding and Combating Russian and Chinese Influence Operations. [online] Center for American Progress. Available at: https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/security/reports/2019/02/28/466669/understand i ng-combating-russian-chinese-influence-operations/.

Lim, G. (2019). Disinformation Annotated Bibliography. [online] Available at: https://citizenlab.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Disinformation-Bibliography.pdf.

Manor, I. (2020). Russia’s Digital Kiev Offensive. [online] Exploring Digital Diplomacy. Available at: https://digdipblog.com/2020/11/05/russias-digital-kiev-offensive/

Mee, G. (2021). What is a Good Engagement Rate on Twitter? [online] Scrunch. Available at: https://scrunch.com/blog/what-is-a-good-engagement-rate-on-twitter.

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation (2020) [Twitter] 27 January. Available at: https://twitter.com/mfa_russia/status/1221898908634361863.

Nemr, C. and Gangware, W. (2019). Weapons of Mass Distraction: Foreign State-Sponsored Disinformation in the Digital Age. Park Advisors. [online] Available at: https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Weapons-of-Mass-Distraction-Foreig n-State-Sponsored-Disinformation-in-the-Digital-Age.pdf.

Nye, J.S. (2013). Hard, Soft, and Smart Power. Oxford Handbooks Online. Oxford University Press

Nye, J.S. (2011). Power and foreign policy. Journal of Political Power, 4(1), pp.9–24.

Oh, S. and Adkins, T. (2018). Disinformation Toolkit. [online] Available at: https://www.acbar.org/upload/1531388417906.pdf.

Osipova-Stocker, Y. (2021). Addressing disinformation: Playing defense is no longer enough. [online] US Agency for Global Media. Available at: https://www.usagm.gov/2021/03/17/addressing-disinformation-playing-defense-is-nolonger-enough/.

Polyakova, A. (2019). US Efforts to Counter Russian Disinformation and Malign Influence. [online] Brookings. Available at: https://www.brookings.edu/testimonies/u-s-efforts-to-counter-russian-disinformation-and -malign-influence/.

Powers, S. and Kounalakis, M. eds., (2017). Can Public Diplomacy Survive the Internet? Bots, Echo Chambers, and Disinformation. [online] US Department of State. Available at: https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/2017-ACPD-Internet.pdf.

Putin, V. (2020). Vladimir Putin: The Real Lessons of the 75th Anniversary of World War II. [online] The National Interest. Available at: https://nationalinterest.org/feature/vladimir-putin-real-lessons-75th-anniversary-world-wa r-ii-162982.

Robinson, O., Coleman, A. and Sardarizadeh, S. (2019). A Report of Anti-Disinformation Initiatives. [online] Programme on Democracy & Technology. Available at: https://demtech.oii.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/93/2019/08/A-Report-of-Anti-Disin 23 formation-Initiatives.pdf.

Rosenberg, P. (2017). Don’t think of a rampaging elephant: Linguist George Lakoff explains how the Democrats helped elect Trump. [online] Salon. Available at: https://www.salon.com/2017/01/15/dont-think-of-a-rampaging-elephant-linguist-george-l akoff-explains-how-the-democrats-helped-elect-trump/#.WH-5mgdzjJM.facebook.

Sargeant, M. (2021). Russia’s Hybrid War in Ukraine: Historical Revisionism and “Twiplomacy.” [online] Small Wars Journal. Available at: https://smallwarsjournal.com/jrnl/art/russias-hybrid-war-ukraine-historical-revisionismand-twiplomacy.

Subcommittee Hearing 116-275 (2020). The Global Engagement Center: Leading the United States Government’s Fight Against Global Disinformation Threat. US Government Publishing Office. [online] Available at: https://www.foreign.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/03%2005%2020%20--%20The%20Globa l%20Engagement%20Center%20Leading%20the%20United%20States%20Governments %20Fight%20Against%20Global%20Disinformation%20Threat.pdf.

Svárovský, M., Janda, J.J., Víchová, V., Gurney, J. and Kröger, S. (2019). Handbook on Countering Russian and Chinese Interference in Europe. [online] Kremlin Watch, Konrad Adenauer Stiftung, pp.4–12. Available at: https://www.kremlinwatch.eu/userfiles/handbook-on-countering-russian-and-chinese-inte rference-in-europe.pdf.

US Department of State. (2020). Briefing With Special Envoy Lea Gabrielle On the GEC Special Report: Pillars of Russia’s Disinformation and Propaganda Ecosystem. [online] Available at: 24 https://2017-2021.state.gov/briefing-with-special-envoy-lea-gabrielle-on-the-gec-specialreport-pillars-of-russias-disinformation-and-propaganda-ecosystem/index.html.

US Department of State. (2019). 2019 Comprehensive Annual Report on Public Diplomacy and International Broadcasting. [online] Available at: https://www.state.gov/2019-comprehensive-annual-report-on-public-diplomacy-and-inter national-broadcasting/.

US Department of State. Functional Bureau Strategy Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs. (2018). [online] Available at: https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/FBS_ECA_UNCLASS-508.pdf.

US Department of State. (2021). Global Engagement Center. [online] Available at: https://2017-2021.state.gov/bureaus-offices/under-secretary-for-public-diplomacy-and-pu blic-affairs/global-engagement-center/index.html.

Vilmer, J.-B. (2021). Effective state practices against disinformation: Four country case studies Hybrid CoE Research Report 2 COI HYBRID INFLUENCE. [online] Available at: https://www.hybridcoe.fi/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/20210709_Hybrid_CoE_Research _Report_2_Effective_state_practices_against_disinformation_WEB.pdf.

Voice of America. (2019). Poland Snubs Russia Before World War II Commemoration. [online] Available at: https://www.voanews.com/europe/poland-snubs-russia-world-war-ii-commemoration.

Walker, C. and Ludwig, J. (2017). The Meaning of Sharp Power. [online] Foreign Affairs. Available at: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/china/2017-11-16/meaning-sharp-power.

Walker, C. (2018). What Is “Sharp Power”? | Journal of Democracy. [online] Available at: https://www.journalofdemocracy.org/articles/what-is-sharp-power/.

Walker, V. and Baxter, S. (2019). Comprehensive Annual Report on Public Diplomacy & International Broadcasting: Focus on FY 2018 Budget Data. [online] US Department of State. Available at: https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/2019-ACPDAnnual-Report.pdf.

Walker, V., Walsh, R., Advisor, S. and Baxter, S. (2020). Public Diplomacy and the New “Old” War: Countering State-Sponsored Disinformation. U.S. Advisory Commission on Public Diplomacy Co-Authors: Transmittal Letter 2. [online] Available at: https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Public-Diplomacy-and-the-New-OldWar-Countering-State-Sponsored-Disinformation.pdf.

Zimmerman, J. (2017). Liberals, Lay Down Your Facts and Pick Up a More Useful Weapon: Emotions. [online] Slate Magazine. Available at: https://slate.com/technology/2017/02/counter-lies-with-emotions-not-facts.html.